Author: Richard R. Tryon

The body of this chapter was scanned from the 1977 publication in which it appeared. It produced, at the time, no special response from any teachers or leaders in the field of education in general, or reading in particular.

To be sure few, if any educators at that time, understood or had an opportunity to 'look into' the human brain to see it at work building the mylinated circuits needed for it to function as the engine to perform the task of reading. All knew that children learned to speak with little formal training, and early teaching of phonics came to be seen as obsolete and boring for children of a modern age. Surely, the tide was moving toward 'whole language' systems. They were right brain dominant, but few understood that or what it meant.

It may not be universal, but probably someone has found out that female teachers tend to prefer right brain thinking with pictures rather than building via the logic of the left brain, the skill of decoding spoken words so as to 'see' them in print. It is not hard to conclude that those who tended to be right brain dominant, could wonder if perhaps the 'whole language' system would be more interesting to study? It is to adults! But, not to the mind of a child trying to unlock the mystery and learn how to determine the meaning of letters grouped together. To be sure, commonly seen words are easy to store in memory as pictures. Indeed, we can even associate the memory picture of a cat with the picture of the three letters. We do the same with a log, but then fail to understand the letters put together to be 'catalog'. The phonic skill of learning the phonemes that are letter combinations that make up the sounds of words is very useful. Children are very willing to spend the boring time required to repetitively perform the tasks until their brains have mylinated the needed circuits to be useful.

One of the most extreme views on the advantages of whole language was taken by a group in Australia that were clearly correct in their conclusion. If reading can be taught with a one-on-one teacher and student approach, then whole language is no longer too frustrating to learn! The teachers memory can keep refreshing that of the student until all of the words are memorized as pictures. The most useful additional skill is to learn to be willing to guess what the strange word must be! Don't worry if the missing adjective is not the one you guess in the context, it will be 'close enough' to allow some level of comprehension, albeit with a tendency to remember the wrong picture for the word guessed!

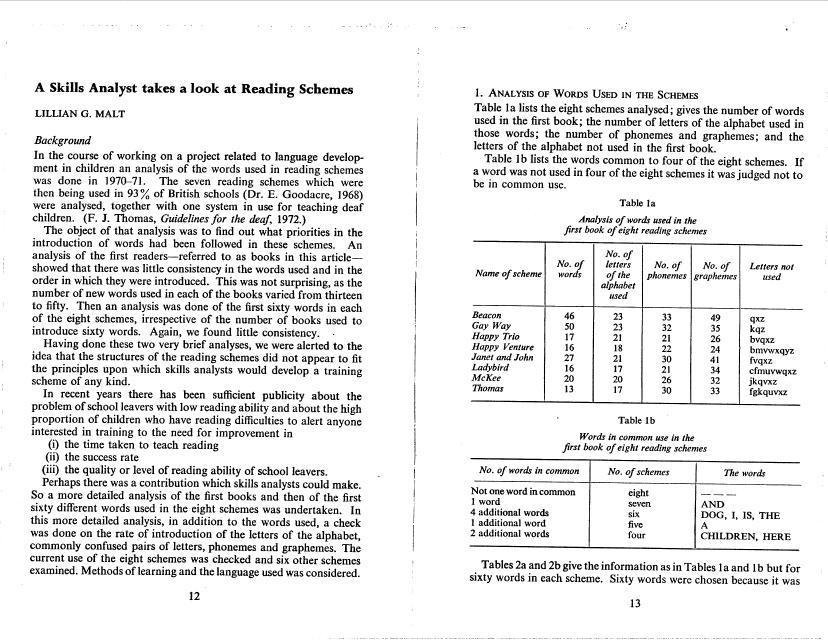

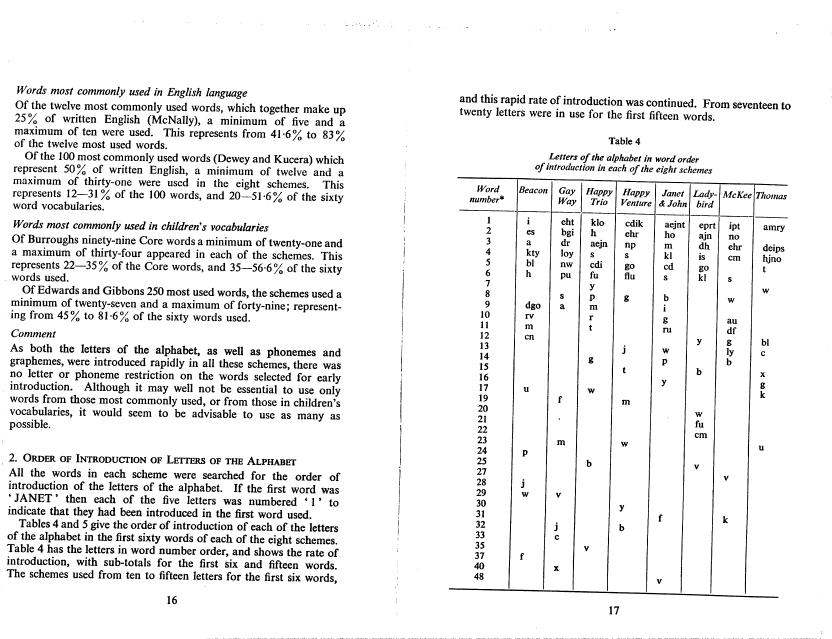

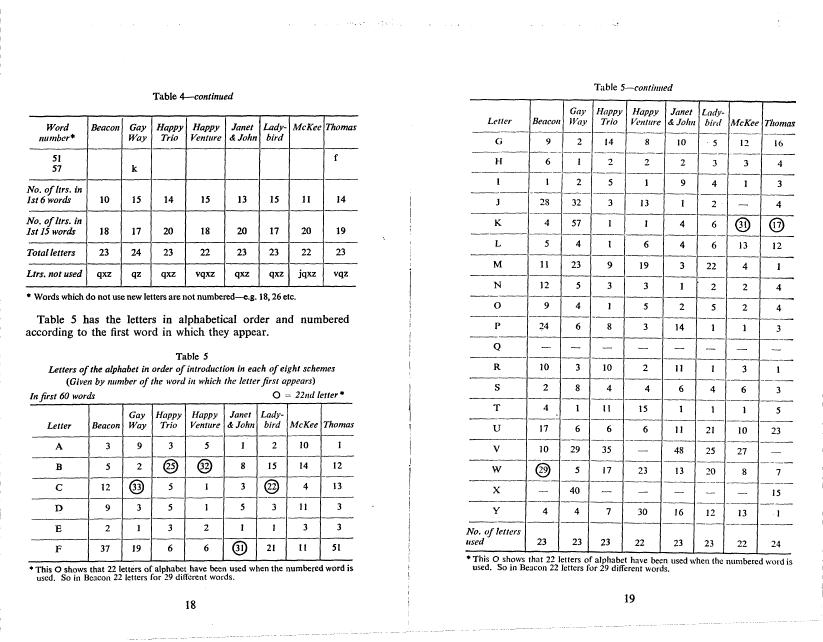

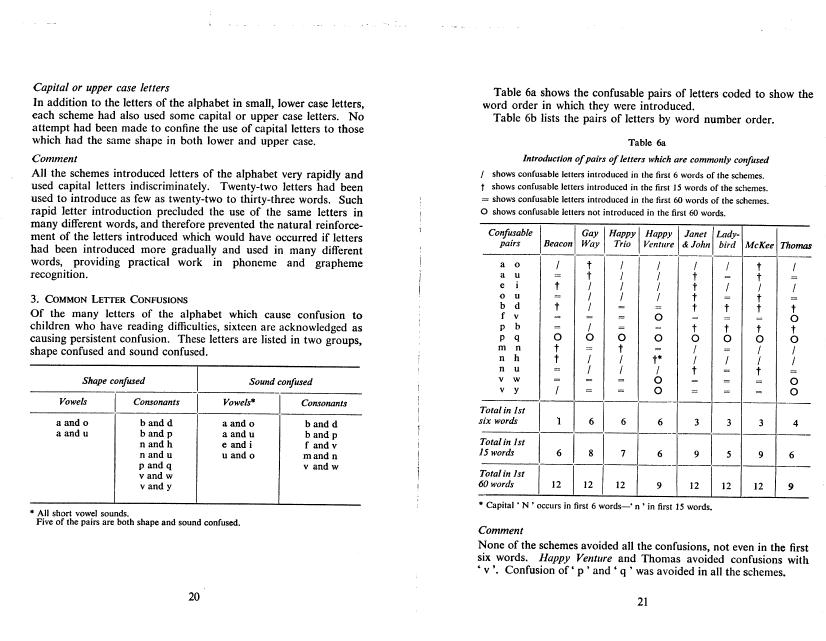

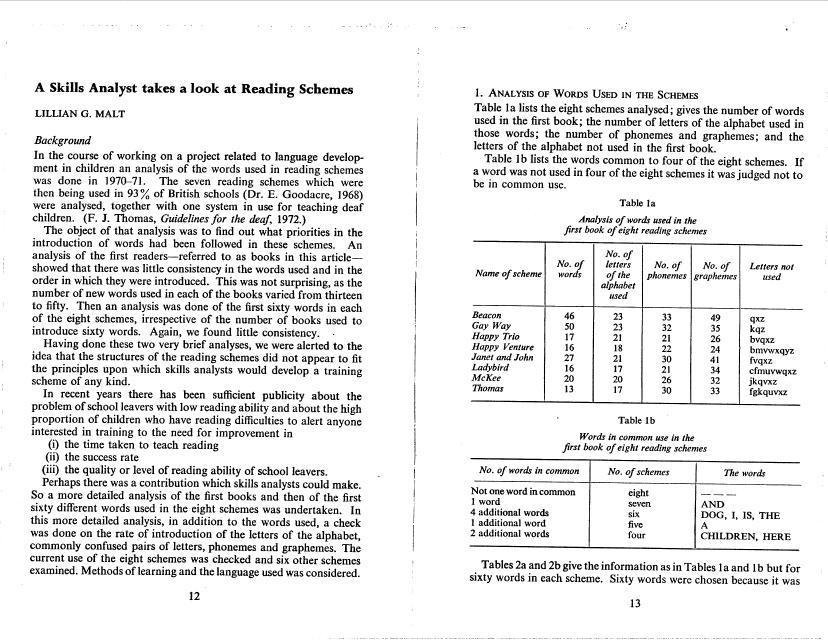

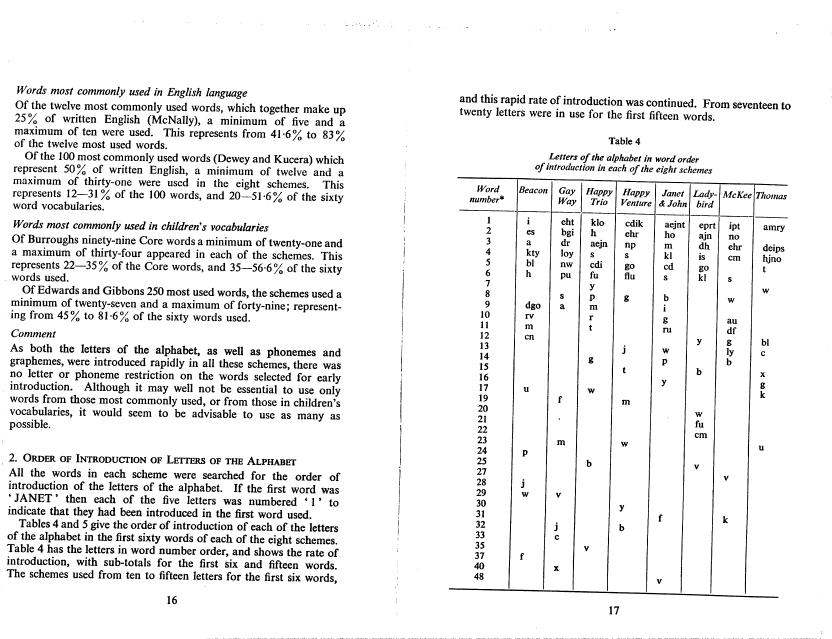

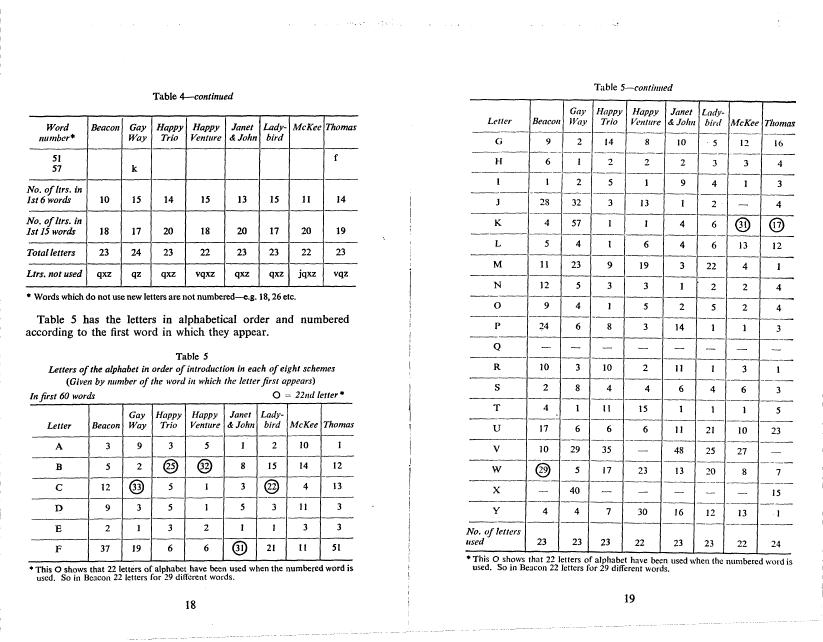

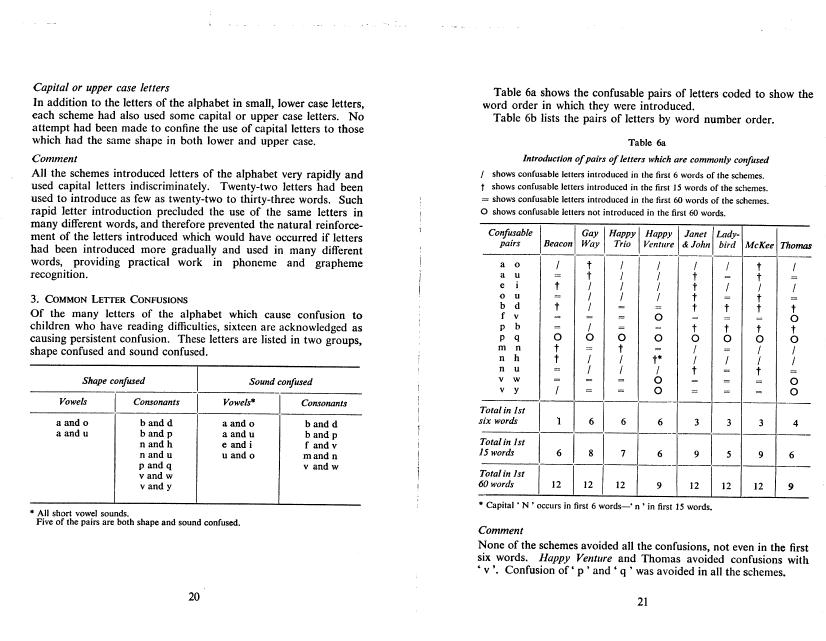

Lillian Malt may have been the first to publish the basic discovery of how we must mylinate circuits that let us combine the visual images before us with the stored knowledge of the sounds of spoken words. By using phonic clues or phonemes we can combine them with stored memory of words that defy logical construction, to learn to read faster and with greater competence.

Here is her precient message:

| Previous Chapter | To TOC | Next Chapter |