“Victoria”

and

“Camperdown”

Catastrophe

by Captain Donald Mcintyre

On a clear Mediterranean day in 1893 three hundred and.eighty-hve men drowned because of rigid and blind obedience to orders.

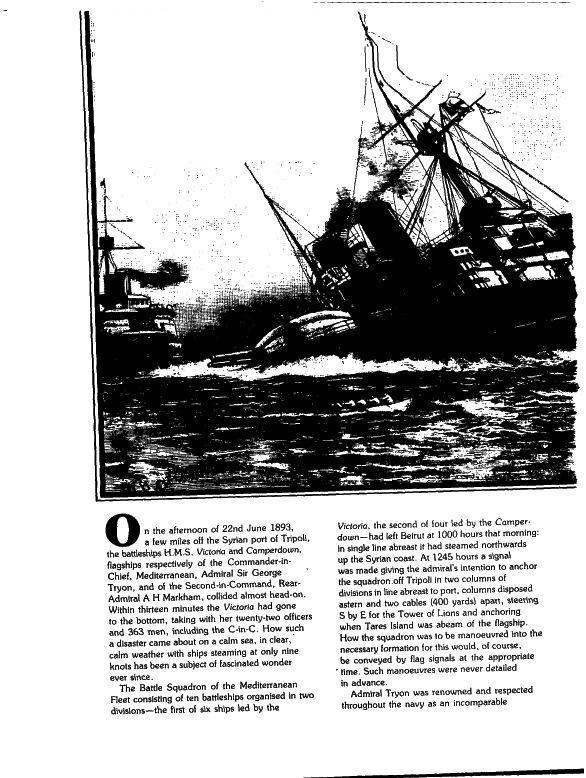

On the afternoon of 22nd June 1893 a few miles off the Syrian port of Tripoli, the battleships H.M.S. Victoria and Camperdown flagships respectively of the Commander-in- Chief Mediterranean Admiral Sir George Tryon, and of the Second-in-Command, Rear- Admiral A H Markham, collided almost head-on, Within thirteen minutes the Victoria had gone to the bottom, taking with her twenty-two officers and 363 men including the C-in-C. How such a disaster came about on a calm sea, in clear, calm weather with ships Steaming at only nine knots has been a subject of fascinated wonder ever since.

The Battle Squadron of the Mediterranean Fleet consisting of ten battleships organised in two divisions—the first of six ships led by the Victoria, the second of four led by the Camperdown—had left Beirut at 1000 hours that morning: in single line abreast it had steamed northwards up the Syrian coast. At 1245 hours a signal was made giving the admiral’s intention to anchor the squadron off Tripoli in two columns of divisions in line abreast to port. columns disposed astern and two cables (400 yards) apart, steering S by E for the Tower of Lions and anchoring when Tares Island was abeam of the flagship How the squadron was to be manoeuvred into the necessary formation for this would, of course, be conveyed by flag signals at the appropriate time. Such manoeuvres were never detailed in advance.

Admiral Tryon was renowned and respected throughout the navy as an incomparable master of close order handling of a fleet. He advocated such exercises as good training for battle, which at that date was still visualised by many naval tacticians as likely to involve gunnery duels between battleships at a range of a few thousand yards. Shortly after 1400 hours on that fateful day Flag Captain Maurice Bourke and the squadron navigating officer, Staff- Commander Thomas Hawkins-Smith came to Tryon’s cabin in the stern of the Victoria, the latter bringing the relevant charts. After the navigator had indicated the squadron’s position and route, the Admiral explained the manoeuvres he intended.

He would first form the squadron into two divisions in line ahead disposed to port (i.e. the Second Division to port and therefore to seaward of the First), six cables (1,200 yards) apart on a course E by N. In this formation the squadron would steam on past the anchorage far enough to initiate the next manoeuvre, which was to reverse course by the two columns turning 180 degrees inwards in succession. The ships would then be so formed that, on the flagship reaching the correct bearing from the Tower of Lions, by altering course 90 degrees to port simultaneously they would be in the anchoring formation. At a signal from the flagship when Tares Island came abeam to starboard, all ships would drop anchor simultaneously.

This series of movements was perfectly feasible, though calling for some skilful handling by individual captains of a number of ships of different design and different turning circles, but for one vital factor: with columns six cables apart there was not sufficient room for the inward turn. The diameter of the turning circle of each flagship which would lead her column into that turn was 800 yards using the three-quarters helm normal in manoeuvring or 600 yards under full helm. In either case they would collide before they could complete the turn. If the two divisions were to be two cables apart on completion of the turn—which was presumably the admiral’s intention —the starting distance using normal manoeuvring helm had to be at least ten cables (2,000 yards).

Hawkins-Smith saw the flaw in Tryon’s manoeuvring plan; but for some reason he suggested eight cables. Even that distance would bring the two flagships alongside one another on completion of the turn unless full helm was used, probably aided by going astern on one engine. The Admiral nevertheless agreed to eight, upon which the Staff Commander went back to the bridge with his charts. Yet when the Flag Lieutenant, Lord Guillford entered the cabin to be given the order for the necessary signal to be made, the admiral again stipulated six cables, emphasising this with a slip of paper on which he wrote the figure 6. Captain Bourke pointed out that he had agreed to eight, but Tryon merely said “Leave it at six” to the Flag Lieutenant who left to have the flag signal hoisted. Bourke then followed the Admiral on to his stern-walk where he reminded him that the Yictoria’s turning circle was 800 yards, only to be told that the distance should remain at six cables. This was queried yet again, making four times in all, when the Flag Lieutenant returned to say that the Staff Commander, on seeing the signal hoisted, had sent him to get confirmation; but no change was made; and at 1420 hours the squadron was duly formed up in two columns six cables apart, the First Division, led by the Yictoria to starboard of the Second, led by the Comperdown.

Disaster was not yet inevitable, however, Rear-Admiral Markham in the Comperdown as well as the captains of every other ship of the squadron, on seeing a signal hoisted ordering an impracticable manoeuvre, could query it by hoisting the answering pennant “at the dip” — half-way up to the yardarm. Until it was hoisted “close-up”, indicating that the signal was understood and that the ship concerned was prepared to carry it out, the flagship could not “execute” the order by hauling down the flag hoist. And when at 1524 hours the signal, addressed to the two divisions individually, to turn 180 degrees in succession, the First Division to port, the Second to starboard (i.e. inwards) was hoisted, this is just what they did.

On the bridge of the Camperdown there was first no doubt that a mistake had been made. When the signal was reported to the Rear-Admiral by his Flag Lieutenant, he said: “It is impossible, as it is an impracticable manoeuvre”; and he ordered his own flag hoist (repeating the signal to his division) to be kept “at the dip”. When Captain Johnstone of the Camperdown asked for guidance he was told: “lt is all right. Don’t do anything, I have not answered the signal.” Markham then told the Flag Lieutenant to have a semaphore signal made to the Victoria querying the flag hoist. But already a semaphore signal from the fleet flagship had been taken in—the daunting message from an impatient superior: “What are you waiting for?” Markham dictated the reply: “Because I do not quite understand the signal”. But worse had meanwhile occurred: the Camperdown’s distinguishing pennants had been hoisted by the Victoria announcing to the whole fleet that Markham’s flagship was at fault. The Rear Admiral’s nerve broke.

Just as Bourke, Hawkins-Smith and had been too over-awed by the prestige and reputation of Tryon to protest with any real vigour about the distance apart of the columns ordered, so several captains who had held their answering pennants at the dip hastily hoisted them close up, assuring themselves, as they were to say in evidence later, that although a mistake had apparently been made, the Commander-in-Chief intended something that would rectify it. Others were more specific: they persuaded themselves that, as two distinct signals, one to each of the Divisions, had been hoisted, the C in C must intend to delay the Victoria’s turn sufficiently to lead th 1st Division round outside the Camperdown.

This was the conclusion to which Markham later stated he also came. The fact that such a manoeuvre could not have brought the fleet to its anchorage in the formation intended did not then or later apparently affect this belief. It would, in fact, have put the fleet flagship to seaward of the junior division and its subordinate flagship—a situation almost unthinkable when anchoring in a foreign port with ceremonial visits between the C-in-C and shore notibilities to be exchanged. So Markham ordered his own flag hoist to be hauled close up. At once the Victoria’s two flag hoists came down with a run. In the Camperdown Captain Johnstone ordered the manoeuvring helm of twenty-eight degrees: the ship began its ponderous swing to starboard, the time was 1528 hours, just four minutes since the signal had been hoisted in the fleet flagship.

On the Victoria’s fore bridge, 1200 yards away, the Commander-in-Chief, Flag Captain, Staff Commander and Flag Lieutenant stood together in a little knot. Nothing further had been said about the distance between the columns. Hawkins-Smith was later to say that his advice was never asked for, “nor did I ever think of giving it on that subject”. Tryon, supremely confident, had treated Markham’s hesitancy with a contemptuous: “What’s he waiting for?” followed by the order to hoist the Camperdown’s pennants and to make the impatient semaphore message. Now he growled: “Go on.” Hawkins- Smith ordered the helm to be put hard over.

Only after this had been done and the ship was well into her turn did Bourke venture to remark to the Admiral: “We had better do something; we shall be too close to that ship.” Getting no reply, he told the midshipman of the watch to take the Camperdown’s distance by sextant angle. The latter gave it as 3 1/4 cables. Bourke thought this was an under-estimation, but he now asked the Admiral’s permission to reverse the port screw (to reduce the turning circle), This he had to repeat two or three times before he got a “Yes” from Tryon, when he at once gave the order. Collision being by this time imminent, he followed it by putting the starboard telegraph to “Full Astern” also and had the ominous order piped: “Close all watertight doors.” There was nothing more he could do, though it was to be suggested that he might have reversed his helm and so, at least, have reduced the angle of impact.

By this time, with the two ships almost head-on to one another and some two cables (400 yards) apart, the inevitability of collision had been borne in on Markham also. From the moment of putting over his wheel he had been watching the helm signals of the Victoria— cones which, hoisted on each of the two yardarm halliards, indicated the position of, her helm. Influenced by his idea that the First Division would be led outside the Second, he had expected to see them show that, after initially putting her helm hard over, the Victoria had eased it, so increasing the turning circle. This had not happened, however; and now the same series of orders as in the Victoria were given in the Camperdown : reverse the inner screw, close watertight doors and then full astern on both engines.

But it was all too late. Inexorably the armour-clad leviathans turned and advanced towards each other while all on deck stood paralysed, watching. With a screech of riven plates, the Camperdown’s steel-sheathed ram was thrust into the starboard side of the Victoria’s forecastle, tearing a huge hole and crumpling up the latter’s deck. For a while the two ships lay thus locked together until the Camperdown her engines still going astern, drew clear, the sea flooding furiously into her luckless victim which began to settle down by the bows and heel over to starboard.

The fatal nature of the damage was not realised in the Victoria. Captain Bourke went below to see to the closing of watertight doors, presumably because the ship’s executive officer, Commander John Jellicoe, was on the sick list and confined to his cabin. On the bridge, Hawkins-Smith, asked by the Admiral whether he thought the ship would stay afloat, said he thought she would as she had been struck so far forward, and he suggested she should be steered shorewards into shallow water. Tryon agreed and the telegraphs were put to half-speed ahead both engines. A signal was to swing her to a southerly heading and then half speed ahead both engines. A signal was made to the squadron annulling a previous to send boats.

It was false optimism, however. Bourke found doors and scuttles shut abaft the scene of the damage and was told by the Fleet Engineer that all was watertight abaft the foremost boiler room and that there was no water in the engine room whence the sound of the telegraph gongs and the working of the engines could be heard. But the engineers, standing manfully to their posts, were locked in a deadly trap by these precautions. As Bourke, on his way to report, reached the upper deck, where most of the remainder of the ship’s company had assembled on the port side, there was a sudden lurch as the ship began to roll over to starboard, then capsized and sank by the bows.

On the upper deck, where the men had remained in disciplined ranks under their officers the order to abandon ship was given at the last moment and was obeyed without a sign of panic. Some were sucked under by the sinking ship and drowned; others were struck and killed by the still-turning propellers as the stern reared itself up before sliding beneath the sea. Many survived and were picked up by boats from the squadron. But there was no hope for those in the engine and boiler rooms and all were lost.

Of the ‘command” on the Victoria’s bridge, only Sir George Tryon was lost. His last words, as reported by Hawkins-Smith and Gulford were: “It’s all my fault.” But over the following months and, off and on, ever since, who or what was to blame for so astonishing a disaster has been the subject of much discussion.

A month later, in accordance with naval custom and regulations of the time, a court-martial assembled on the quarterdeck of the old three-decker Hibernia at Malta where she served as flagship of the Admiral Superintendent of the Dockyard, to try the survivors of the sunken ship. In fact, by agreement of the court, Captain Bourke appeared as the only accused on behalf of them all, Presiding over the court comprising the Admiral Superintendent and seven post-captains, was the new Commander-in- Chief, Admiral Sir Michael Culone-Seymour; the Prosecutor was Captain Alfred Leigh Winsloe.

So, between 17th and 27th July 1893, in the stifling, humid heat of a Maltese summer, the tragic story was told, examined and re-examined. Much of the evidence concerned technical details to do with the damage sustained by the Victoria and the causes of her foundering and the conduct of the officers and men of her company which, it was agreed, had been in all cases in accordance with the highest traditions of the Service. Here we are concerned only with the dual question of how so acknowledged a master of manoeuvre Sir George Tryon could, at his own confession, have made so basic an error in ordering the fatal manoeuvre, and how his second-in- command his Flag Captain allowed the to be persuaded into attempting to carry it out against their own judgment.

In the absence of any evidence from Tryon himself, the answer to the first of these questions must always be a matter of speculation. That his mistake was due to some form of mental aberration is clear. An idea which had gained currency was that Tryon had in some way confused the diameter of the turning circle with the radius. Neither Bourke nor Hawkins-Smith subscribed to this when questioned by the court. The former, indeed, seemed incapable of imagining that his revered Chief, “whose experience was far-reaching, and whose vast knowledge of the subject of manoeuvre was admitted by all”, could make such an error.

Nevertheless, one who later studied and about the disaster—Commander R T Gould in a book called Enigmas—quoted an admiral who, as a captain, had served under Tryon in the Channel Fleet and had had a similar experience. In his case, however, he had resolutely refused to hoist his answering pennant close-up and eventually the manoeuvre had been cancelled because the squadron was approaching the land. At the time he had been reprimanded; but when dining with the Admiral later had received a grudging admission that he had been right. From this it is clear that even such a master of the manoeuvre as Tryon could make fatal mistakes.

We are left with the question of how Bourke and Hawkins-Smith on the one hand, Markham and Johnstone on the other, could have deliberately initiated a movement which they knew could only end in catastrophe. Bourke’s reminder to Tryon both of his original agreement to eight cables as the distance at which the two divisions should start the inward turn, and of the turning circle of the two ships, given in evidence, gained impressiveness by his loyal attempt to avoid testifying to what had passed between him and the dead admiral. Asked to give a reason for not taking more positive action, he said he felt sure that the Commander-in-Chief ‘had some way out of it”. His emotional defence and his appeal to the court to appreciate the difficulty of his position at the side of so overpowering and respected a superior as Tryon gained the court’s sympathy.

As the trial progressed, indeed, it was Markham and Johnstone, examined at length, who gradually assumed the position of the real accused. Although the Rear-Admiral’s first reaction to the fatal signal had been: “It is impossible; it is an impracticable manoeuvre”, his weakness in persuading himself that there was a feasible method of obeying it (the First Division

circling round his command) was clearly exposed. It was a method that called for strict conformity and no initiative on his part. Johnstone, too, admitted that his first thought was that a signal had been made but that he came round to his admiral’s way of interpreting it. In any case, he stated, once the turn was started, the junior divisional leader (H.M.S. Camperdown) had no choice but to obey the signal strictly:

any independent move had to be by the 1st Division and this was re-inforced by the Rule ot the Road which called for two ships approaching head-on to alter course so as to pass port side to port side. This could only have been by the Victoria easing or reversing her helm and enlarging her turning circle. Any such alteration by the Camperdown was fraught with all sorts of imponderable dangers.

Other captains, called to give evidence as to their reactions, stated they had come to the same conclusions as Markham and could, at the time, see no other explanation, though all had at first assumed a signal mistake had been made. The one thing that most clearly emerged was that after an initial hesitation while they puzzled out an explanation, the thought never crossed the minds of the Rear-Admiral or either of the two captains chiefly concerned that the Commander-in-Chief could be unaware that his order, must result in collision between the two flagships. So indoctrinated were they with the system of discipline, in which they had been brought up, that they could not bring themselves to criticise, let alone disobey an order, even though they could not understand or justify it.

Tryon himself had evidently sensed this danger. The Prosecutor introduced in evidence a memorandum which had been promulgated to the Fleet in the previous May. This quoted memorandum by the Duke of Wellington in 1803 in which he reminded his officers that an order may be given which, from circumstances not known to the person who gave it at the time he issued it, would be impossible to execute . . . Tryon’s memorandum then went on to caution the officers of the Fleet that “Orders directing the movement of ships either collectively or singly are invariably accompanied, as a matter of course, with the paramount understood condition: - ‘With due regard to the safety of H.M. Ships’.”

That such a memorandum should have been necessary is an indication of the state of iron-bound, unquestioning obedience to the orders of a superior into which the Royal Navy had been moulded, while at the same time paying almost religious homage to the memory of that exemplar of reasoned insubordination—Horatio Nelson.

It had not been enough, as the Victoria and Camperdown catastrophe tragically demonstrated. Nevertheless, that catastrophe could have led to a reform of the naval system of rigid conformity and unquestioning reliance upon a senior’s judgment. The outcome was in fact quite different. Captain Bourke was completely exonerated by the Court. Rear-Admiral Markham and Captain Johnstone, who were not on trial, were criticised, the latter being relieved of his command not for attempting to obey an impracticable and dangerous order, but for not in good time taking such “precautions” as reversing the inner screw and ordering the closing of watertight doors.

So the Royal Navy persisted in its hide-bound attitudes. Twenty-three years later, at the Battle of Jutland, the chance of a decisive Britisih victory was missed when the British Commander- in-Chief, by a brilliant tactical manoeuvre, trapped the inferior German fleet, only to have the fruits snatched from his hand; firstly through subordinate admirals refusing to take independent action against the enemy clearly their sights in the absence of an order from above; and secondly through the failure of subordinates to keep the C-in-C informed of the situation in their vicinity, unable apparently to doubt that all must be known to the god-like creature on the bridge of the fleet flagship, even though he was groping hazily through the North Sea mist and the fog of battle.

The Commander-in-Chief concerned? Admira Sir John Jellicoe, a survivor from the Victoria.

Author Captain Donald Macintyre served as an Escort Group Commander in the Battle of the Atlantic, and retired from the Royal Navy in 1954 to write history and biography. His first book was the autogiographical U-Boat Killer, and other works have included a biography of Admiral Rodney, an account of the Battle of Jutland, and several books on naval subjects.

Further Reading:

Enigmas, by Commander R.T. Gould

Admirals in Collision, by Richard Hough.

Minutes of Proceedings of Court Martial Held on Board

Her Majesty’s SHIP “HIBERNIA” AT MALTA TO ENQUIRE

INTO THE LOSS OF HER MAJESTY’S SHIP “VICTORIA”.

(Public Record Office)